In

this part of the world, they talk of having 27 centuries worth of history.

Now

most places have lengthy histories, but if that sounds like an exaggeration, it

isn’t.

And

nothing could have made that clearer than a board charting those centuries in

timeline form, which hangs in a small room off the cloister at the Cathédrale

in Elne.

Originally

under the control of the Ibéres, the town was first known as Pyréne, then

Illibéris, during which time, in 218 BCE, Hannibal dropped in for a break after

crossing the Pyrenees.

The

Romans liked it so much that they came, saw, conquered and stayed around for a

while, from 118 BCE to 414 CE, during which Elne became Castrum Helenae.

Then

the Visigoths came, replaced by the Arabs for around 70 years, and followed by

the Carolingians for just over a century.

By

the time the Catalans took over in 873, it was Elna. Then the French popped

over in 1473 before the Spanish arrived in 1494, to be replaced by the French

again in 1642 when they realised they rather liked the place and would keep it.

And so the town became Elne.

It

was the bishopric of Roussillon from the 6th century, but as nearby

Perpignan prospered, Elne declined. In the late Middle Ages, the counts of

Roussillon moved their seat there, with a papal bull seeing the Episcopal seat

follow in 1601.

It

was the bishopric of Roussillon from the 6th century, but as nearby

Perpignan prospered, Elne declined. In the late Middle Ages, the counts of

Roussillon moved their seat there, with a papal bull seeing the Episcopal seat

follow in 1601.

The

Cathédrale Sainte-Eulalie-et-Sainte-Julie was founded in 1060 and consecrated

nine years later, a lasting monument to the Roman style of architecture, with

its two towers soaring above the town from the old ville haute.

The

cloister is one of the finest examples of the Roman style – and now, centuries

later, is one of the major drawing points for tourists, as Elne slowly starts

to benefit from the rise in tourism – and the development of an area that, not

that long ago, was considered the poor man of France.

And

that cloister is astonishing.

It

isn’t exaggerating to say that one could almost sense monks walking around,

their habits rustling almost imperceptibly. The more imaginative could even be

forgiven for thinking they hear the sound of chant on the breeze that brushes

the lavender in the quadrangle.

The

cloister developed from the Greek and Roman peristyle, or open porch,

frequently surrounding an internal garden, and here, the colonnaded shade and

the Mediterranean sun present sharp contrasts.

The

cloister developed from the Greek and Roman peristyle, or open porch,

frequently surrounding an internal garden, and here, the colonnaded shade and

the Mediterranean sun present sharp contrasts.

The

carvings that decorate columns and walls run from the Romanesque to the Gothic,

and besides showing Biblical scenes, also include flowers and patterns,

together with mythical creatures, including griffins and mermaids.

The

church itself is interesting too, with its Romanesque vaulted ceiling –

rounded, not rising to a point. There are the usual side chapels and statues

and candles, but nothing quite to equal the cloister.

|

| Carvings of griffins. |

We

had taken the bus from to Elne and wandered upward, into the haute ville, the oldest and highest

parts of the town, which surround the Cathédrale.

This

small area offers extraordinary views across the plain to the Pyrenees as they

slope gently down to the sea at Collioure, and to Perpignan and the Corbières

hills in the other direction.

There

were geographic advantages to Elne as a point from which to rule.

Next

to the tourist information office was an old building that housed the gallery

and glass-blowing workshop for Sylvain Magney and Veronique Carvalho.

Heaven

alone knows what the heat would have been like if there had been any glass

being blown when we were there, but the artist was having a day’s rest.

The

glass was lovely. I came away with earrings and a pendant, in a sea green, with

bubbles in them, like air rising to the surface. Unique pieces.

|

| Little Zazou. |

Artisanal

crafts are a part of Elne’s revival and, a short while later, as we ambled

among to apparent jumble of Roman walls and later housing, we found a little

artists’ enclave with a café serving regional items – even up to Catalan cola.

As

we sat amongst the palms, we saw a little cat. A sweet-faced thing, with a

touch of mange and very dodgy back legs, one of the craftsmen (he makes harps)

told us that this was Zazou.

At

14, she had been abandoned by her owner for being ‘too old’. Apologising for

his language, he said how disgusting he thought this was. The artists and

craftsmen and women in the café were all making sure that she had food and

water.

“She’s

not ready to die yet,” he added, looking fondly in her direction, as she lay on

the step outside his workshop.

Such

selfishness on the one hand and kindness on the other.

After

the Cathédrale, we headed for lunch, and found ourselves at the very nearby Au

Remp’Arts.

There

we both had jambon and melon for a starter; vast portions of sweet, ripe

fruit and glorious ham, served on little wooden pallets.

There

we both had jambon and melon for a starter; vast portions of sweet, ripe

fruit and glorious ham, served on little wooden pallets.

There’s

a reason that this is such a classic combination: with quality ingredients,

it’s superb.

The

Other Half opted for a steak to follow, while I hunted the menu for the fish.

Spotting

something called ‘cabillaud’, the fact that it was grilled and coming with

aioli suggested that this was in the right area.

Indeed,

it was cod. And very nicely done too, arriving on a bed of garlicky potato

purée, with a piece of crisped skin and two chives as a garnish, and piles of a

sort of julienned version of ratatouille on either side.

With

a three-course deal for €26, desserts were a bit of a letdown. The Other Half’s

crema catalana was closer to scrambled egg than it should have been – Hurrah! I’m not the only one who can scramble a custard!

With

a three-course deal for €26, desserts were a bit of a letdown. The Other Half’s

crema catalana was closer to scrambled egg than it should have been – Hurrah! I’m not the only one who can scramble a custard!

My peach melba

was simply chopped peach with a little vanilla ice cream and a pile of

chantilly cream on top.

But

after two excellent courses, at such a reasonable price, it would have been

churlish to complain.

We

ambled some more as clouds threatened a downpour, and eventually found our way,

via a circuit, back to a gallery that contained a number of works by local

artist, Ètienne Terrus.

The

great advantage of such galleries, as with individual exhibitions of a single

artist, is that get a sense of that artist’s journey.

And

Terrus had certainly been on a massive journey, artistically speaking.

Looking

at works from the late 19th century, there was nothing to suggest

what would follow.

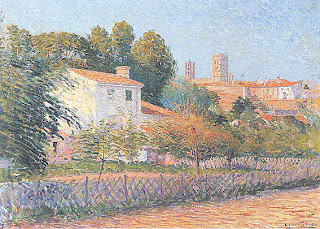

|

| Elne, by Ètienne Terrus, 1900. |

Technically

excellent, but two still lives (of oysters and of a fish with pan) were

reminiscent of Gustave Courbet, in terms of the light and use of colour.

But

then Terrus discovered Impressionism and, with it, a vastly increased palette

of colour.

And

where his work went from there sees him now regarded as a precursor to the

Fauves – the likes of Matisse (a friend) and Derain and Dufy, many of whom

spent much time in Collioure, with which they and their art movement remain

inextricably linked.

After

a combination of religion, food and art, we made our way back to Collioure, via

the hubbub of Argèles sur Mer (great beaches, town built up as the archetypal

resort).

It

had been a fascinating day.

No comments:

Post a Comment