|

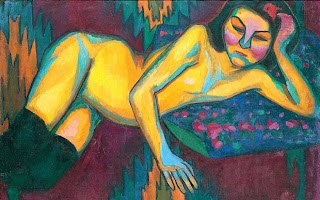

| Yellow Nude (1908) |

This spring has seen the Tate Modern open the first ever UK

retrospective of Sonia Delaunay – and it makes for a fascinating and educative

experience.

Delaunay (1885-1979) was one of the pioneers of abstract

painting and a key figure in the Paris avant-garde, particularly in the early

20th century, and this exhibition gives us the chance to explore the

breadth of her work.

Born in Odessa, at the age of five she went to live with a

wealthy uncle in St Petersburg, before studying art in Germany and then moving

to Paris in 1906 – a year after the sensation-causing, game-changing Fauve

exhibition.

Shortly thereafter, with her somewhat disapproving parents

wanting her to return to Russia, Delaunay married gallery owner Wilhelm Uhde –

probably a marriage of convenience in order to facilitate her stay in the

French capital, given that he was gay.

It worked for both of them: Delaunay gained access to the art

world through Uhde and he was able to wear heterosexual married respectability.

|

| Portrait of Philomème, 1907 |

Sonia met Robert Delaunay via the gallery in 1909. Divorce from

Uhde was finalised the following year and she and Robert were married in the

November, with a son, Charles, born early in 1911.

But so much for the background – now for the work.

Early paintings show the influence of both the Fauves and the

likes of Gauguin – in particular, the superb Yellow Nude (1908),

which echoes both the cloisonnism and colour of the

former’s Yellow Christ and the latter’s use of other colours.

And we can see the same influences in other works, including

several portraits of her dressmaker, Philomène, and a series of paintings of

young Finnish women.

So if you’re not familiar at all with Delaunay’s work – or only

through the later abstracts – then it’s a great way to gain an understanding of

just how good she was. (God, she was better than Derain).

But from the earliest days of her career, she was also working

in non-traditional art forms, and we get a taste of this in the second room:

embroidery, for instance, an abstractly-painted toy box and a patchwork cradle

cover the for the young Charles.

Indeed, Delaunay thought that, after creating it, the cradle

cover ‘evoked Cubist conceptions’.

For many critics, this is the period that the Delaunays – whose

partnership occurred in art as in the bed – create what legendary poet,

novelist and critic Guillaume Apollinaire christened in 1913 as Orphism, the

couple’s own version of Cubism.

It’s one thing, though, to decorate your own home, but entirely

another to take such techniques into the public realm.

Visiting Spain when WWI broke out, the couple decided to stay in

the country. But in 1917, as the Russian Revolution saw financial support from

her family dry up, Sonia took those techniques and started to make money from

them.

Showing great business nous, she started her own company, Casa

Sonia, selling her designs for fashion and interior décor. She also decorated a

casino, designed costumes for Diaghilev for the ballet Cleopatra and also

for opera.

This is a real case of the ‘applied arts’, and remains an

illustration of just how blurred the lines are between the ‘fine arts’ and any

other form of art.

|

| Prismes electriques, 1914 |

It continues: next year, for instance, sculptor Anish Kapoor is

set to design a new production of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde at the

English National Opera, which is part of the selling point of that production.

This was also pretty new terrain for me: there’s a reason I’ve

hardly ever been inside the V&A – I’m not particularly interested in

fashion, textiles and so forth.

But one of this exhibition’s really big pluses is in showing

just how blurred those lines are, and keeping the likes of me interested in the

applications of Delaunay’s art.

There are fashion drawings, rolls and swatches of fabric, and

finished garments – including an extraordinary coat that is rumoured to have

been made for Hollywood star Gloria Swanson: even a bookshelf designed for

student accomodation.

This is not art as elitism.

There are also obvious points at which a venn diagram of this

exhibition and one of last year’s wonderful Matisse cut-outs would overlap –

and that’s excluding the Fauvist influence that I mentioned earlier.

|

| Propeller, 1937 |

Like Matisse, Delaunay worked to link text and image – not least

in illustrating Blaise Cendrars’s poem, La prose du Transsibérien et de la

Petite Jehanne de France. The exhibits also include paintings

of dresses designed with brief poems on them.

In Matisse’s case. A limited number of designs were incorporated

into fabrics such as scarves.

After the war she and Robert returned to Paris and, in 1937, she

produced three vast canvases for the International Exhibition of Arts and

Technology – murals of an aeroplane propeller, an engine and a dashboard.

All of them are exhibited at the Tate Modern: all of them still

feel incredibly modern, not least because of their graphic – and indeed, deeply

technical – approach to their subjects.

Robert died of cancer in 1941, and Sonia dedicated much energy

to looking after his legacy.

Yet there is plenty of work here from after that period too. As

The Other Half noted in the final room, containing works produced in her

eighties, staying active; keeping busy – it makes a difference.

There is plenty here to enjoy and to be educated by.

|

| Bal Bullier (1912-13) |

As I’ve already noted, she took her art into a variety of

applied directions – initially motivated by the need for an income – but the

use of designs for clothing, interiors etc can be argued to increase access to

art and design.

The exhibition includes many examples of her abstracts – it is

intriguing to see how she developed recurring abstract themes over the decades,

changing media and palette – while some works, such as Bal Bullier

(1912-13), illustrate her breaking down of the barriers between the purely

abstract and the purely figurative.

Many of the works have a great sense of rhythm and movement.

All in all, a fascinating exhibition and one that’s well worth

visiting: there’s little that is static here.

I was previously only really familiar with Delaunay from our

visit to the Pompidou last July, but this allowed me to appreciate an extremely

fine artist very much better.

I heartily recommend that you take the same opportunity.

No comments:

Post a Comment